Movie Sundays / Domingos de Cine

It's the country, it's getting dark...

Like every Sunday afternoon, Gertrudis bathed and dressed her two little daughters, before Arnoldo, her husband, woke up from his nap to take them to the movies. This time, Manuelito, the younger brother, would also go because he was already grown up, they had told him. They were seven, six and three years old respectively. Well dressed and with his hair licked by the quinado, the boy had become so absorbed counting the hours and minutes that were left for the show, that he did not eat a bite all day. The Nymph, as the town tram was known, would not take long to arrive, so they had to hurry to be there at the appointed time.

Sataya was still a remote village that did not have basic running water services and even less electricity, so the televisions were still a rumor that came and went with the wind. The only electronic entertainment was two or three battery-operated radios in the homes of the wealthiest families, where for a nickel, the townspeople gathered every afternoon to listen to the news and the frenetic radio soap operas of Chucho, el roto and Porfirio Cadenas, el ojo de vidrio. During the day, the men spent the hours befriending the sun, while working the land or herding and milking cattle in paddocks and corrals; women, for their part, were busy raising their children and housework. Life couldn't be simpler and flatter.

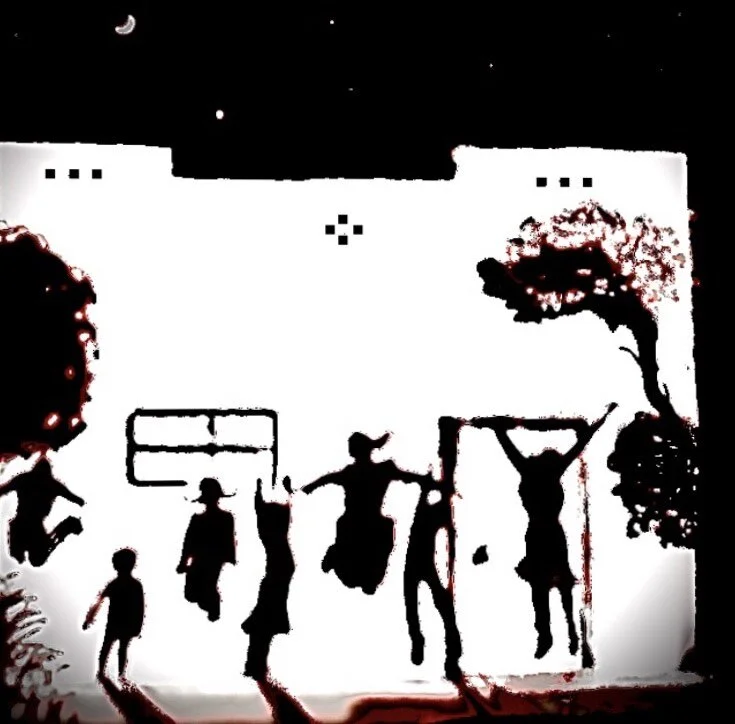

When they were ready, the father took a lit stick from the stove to light the oil lamp that would illuminate them during the journey; he picked up the three colorful little chairs and they walked out onto the main road, the dusty cobbled path that connected the town to the world. Manuelito was silent, containing the emotion accumulated during the week. They arrived at Aunt Queta's house, right at the entrance to the town, where their cousins, Jaimito and his sisters, were already waiting. They arranged their chairs and sat down to wait for the tram, exactly in front of the white facade of the house, which contrasted with the black and starry canvas of the night. This time the wait had been shorter. There in the distance a hole was drawn in the dark, announcing the arrival of the Nymph. With a grand toot it made its appearance, parking in front of the place where the children were anxiously waiting. Arnoldo did his best to keep them seated. The moment the headlights of the tram illuminated the kids and projected their shadows on the white facade, they went crazy playing making figures with them, jumping and running from one place to another. If they were lucky, the show would last five or six minutes, depending on how many people got off at that point and the time it would take to unload the provisions they brought from the city to stock up during the week. When the passengers finally finished getting off and the tram was gone, the children, still not recovering from their fatigue and enchantment, went to bed satisfied.

That night, a strange little light would remain on in Manuelito's head, which would not let him sleep thinking about the days he would have to wait until next Sunday, to go back to the movies and have another memorable night.

Es el campo, está oscureciendo...

Como todos los domingos al caer la tarde, Gertrudis bañaba y vestía a sus dos pequeñas hijas, antes de que Arnoldo, su esposo, despertara de la siesta para llevárselas al cine. Esta vez también iría Manuelito, el hermanito menor, porque ya era grande, le habían dicho. Tenían 7, 6 y 3 años respectivamente. Bien vestidito y con el pelo relamido por el “quinado”, el niño se había quedado tan ensimismado contando las horas y los minutos que faltaban para la función, que en todo el día no probó bocado. La Ninfa, como era conocido el tranvía del pueblo, no tardaría en llegar, por lo que había que darse prisa para estar a la hora convenida.

Sataya era todavía un caserío remoto que no contaba con los servicios básicos de agua potable y menos aún, de electricidad, por lo que las televisiones eran todavía un rumor que iba y venía con el viento. El único entretenimiento electrónico eran dos o tres radios de pilas en casas de las familias más pudientes, donde por cinco centavos, todas las tardes la gente del pueblo se daba cita para escuchar las noticias y las trepidantes radionovelas de Chucho, el roto y Porfirio Cadenas, el ojo de vidrio. Durante el día, los hombres pasaban las horas amigándose con el sol, mientras trabajaban la tierra, o pastoreando y ordeñando el ganado en potreros y corrales; las mujeres por su parte, vivían atareadas con la crianza de los hijos y los quehaceres de la casa. La vida no podía ser más simple y llana.

Cuando estuvieron listos, el padre tomó un tizón de la hornilla para encender la cachimba que los iluminaría durante el trayecto; recogió las tres sillitas de colores y salieron caminando hacia la carretera, el polvoroso camino empedrado que conectaba al pueblo con el mundo. Manuelito iba callado conteniendo la emoción acumulada durante la semana. Llegaron a la casa de la tía Queta, justo a la entrada del pueblo, donde sus primos, Jaimito y sus hermanas, esperaban ya desde hacía rato. Acomodaron sus sillitas y se sentaron a esperar por el tranvía, exactamente frente a la fachada blanca de la casa, que contrastaba con el lienzo negro y estrellado de la noche. Esta vez la espera había sido más corta. Allá a lo lejos se dibujó el hoyo en lo oscuro, anunciando arribo de la Ninfa. Con un gran pitido hizo su aparición, estacionándose frente al lugar donde esperaban ansiosos los chiquillos. Arnoldo hacía hasta lo imposible para mantenerlos ensillados. En cuanto los faros delanteros del vehículo iluminaron a los niños, estos se volvieron locos correteando de un lado para el otro, haciendo todo tipo de figuras con sus sombras que eran proyectadas en la gran pantalla blanca. Si tenían suerte, la función duraría 5 o 6 minutos, dependiendo de cuanta gente bajara en ese punto y el tiempo que tardarían en descargar el mandado que traían de Culiacán para abastecerse durante la semana. Cuando por fin terminaron de bajar los pasajeros y el tranvía se había ido, los niños, sin recuperarse todavía de la fatiga y el encantamiento, se fueron a la cama satisfechos.

Esa noche, una extraña lucecita permanecería encendida en la cabeza de Manuelito, que no lo dejaría dormir pensando en los días que tendría que esperar hasta el próximo domingo, para volver al cine y tener otra noche memorable.